After author Ben Austen released a book on Chicago’s Cabrini-Green public housing complex in 2018, a reader contacted him with information on the high-profile killings of two police officers he’d written about—murders he said marked the beginning of the complex’s “infamy.” The message sparked a years-long investigation.

“Somebody reached out to me and said, ‘Hey, you wrote about that crime in 1970, the 17-year-old who was convicted of that crime, he’s still in prison,’” the reader told Austen. “‘He’s innocent, and he’s coming up for parole.’”

The 17-year-old was Johnnie Veal. He’d been convicted of killing the two officers while they were walking through Cabrini-Green and sentenced to 100–199 years in prison.

“It hadn’t crossed my mind that a 17-year-old in 1970, which is before I was born, would still be sitting in a prison cell nearly 50 years later,” Austen told The Appeal. “I didn’t fathom it. And of course, that’s how our prison system operates. We’re supposed to not think about people. They’re disappeared.”

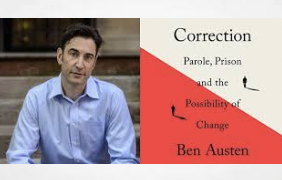

Austen reached out to Veal and soon became immersed in his case and the larger world of parole—which Veal had been repeatedly rejected for since 1980—and chronicles this in his new book, Correction: Parole, Prison, and the Possibility for Change.

By 1927, parole was established in almost every U.S. state. But, between 1976 and 2000, during the so-called “tough-on-crime” era, 16 states and the federal prison system eliminated parole. In the states where parole still exists, Austen said the process can seem like a subjective, arbitrary storytelling contest, in which people must convince a parole board that they’ve changed after entering prison. A person’s freedom can often depend on the board’s mood or makeup.

“Somebody has to talk about why they should be returned to society, that they’re a safe bet, that they’re no longer a threat to society, that they’re remorseful,” he told The Appeal. “And the story that’s always so far out in the lead is the one of the original crime, which is fundamentally unfair because that’s the one thing that never changes.”

Below is The Appeal’s conversation with Austen about his new book. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The Appeal: What is wrong with today’s prison and parole system?

Ben Austen: We don’t actually have a correction system. People who get sent to prison, there aren’t structures in place that work on rehabilitation. People don’t know from day one what they need to do to get out. If we had a true correction system that focused on corrections, parole would be much more prevalent and feel much more effective. We would be celebrating when people get out because they graduated through this program. This happens in other countries.

I visited prisons in northern Europe and everything was focused on reentry from day one. Correctional officers were highly trained in things like social work, psychology, and behavioral science. They were like mentors to the people in prison. They weren’t just like police. They felt a sense of pride in their work when people earned release.

There was a guy on the trip who had been incarcerated in California who cried when he heard that. When he left [prison] the guard said to him, “See you in a month motherf**ker.” They were rooting for his failure and expecting it.

TA: How can a person’s innocence hurt their chance of parole?

Learn more at

https://theappeal.org/history-of-parole-united-states-legal-system/