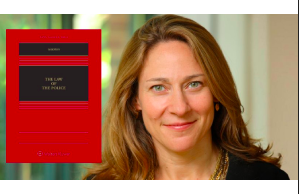

As debates about policing pervade the public conversation, Professor Rachel Harmon of the University of Virginia School of Law has written the first casebook to look at the laws that govern police conduct in the United States.

“The Law of the Police,” published by Wolters Kluwer and available now, takes on the question of how the law shapes police-citizen encounters and how the law might be leveraged to make policing serve the public better.

Harmon, a former federal prosecutor who directs the Law School’s Center for Criminal Justice, has taught a course on the laws governing police for 15 years. She came to UVA Law in 2006 after spending eight years as a federal prosecutor in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division.

Throughout her time in academia, she has wrestled with what role, if any, policing should have in people’s lives, and how best to prevent misconduct.

“I came to the Law School from practice, where I spent years prosecuting civil rights cases, including against police officers,” she said. “Over time, I got frustrated with criminal prosecution as a response to police misconduct. Prosecuting illegal police violence can be important, but I knew there had to be better ways to prevent problems in policing.”

Among her goals for the book, she said, was “to look at how different laws and legal rules make policing more or less harmful.”

The book is a reaction to the traditional approach to policing the police, which is rights-focused. For example, a common police practice she considers problematic is selectively asking drivers, based on a gut feeling, to open their trunks during a traffic stop — with all of the officer’s conscious and unconscious biases in tow.

“Lawyers have typically looked at such problems and argued that they violate Fourth Amendment doctrine or, if they don’t, that the doctrine should be changed,” she said. “I see things differently.”

In the evolution of her thoughts, Harmon first looked at how existing rights and remedies might be applied to curb policing that works against the public interest.

“I spent my first couple of years as an academic looking at legal remedies to see whether they could be used to prevent problems in policing and tossing them over my shoulder,” Harmon said. “So civil rights damages actions, is that going to work? No, that’s not going to work a lot of the time. Justice Department investigations of police departments, is that going to work? No, that won’t work well enough either.”

She then suggested enhancements to these existing tools, before going another way.

“I wrote a couple of articles trying to improve rights and remedies before I started to write about how to think more broadly about police misconduct as a regulatory problem. The question is not only how to remedy police misconduct, but how to use law to get the public safety we want, both through policing and through other means.”

Focusing on that question led Harmon to study the harms of policing and how the law overlooks them or contributes to them.

Moreover, studying the vast array of legal rules that shape policing and police departments led Harmon to realize how little of it lawyers and law students may know, she said.

“Hopefully, the book can be a resource, not just for law students, but for academics, lawyers, police chiefs, journalists, activists, judges or just about anyone interested in how the law actually governs policing and how it might do so differently, whether that’s reforming police departments or turning public safety over to nonpolice actors,” she said.

She noted that the book is different than a criminal procedure textbook, which specifically prepares lawyers for the concepts they will need to know as future prosecutors or defenders. Her book is organized by police practices, such as stopping traffic, using force, maintaining order, and policing resistance and protests, rather than legal categories dictated by Fourth and Fifth Amendment law. The book covers departmental policies and local and state law, as well as federal statutes and cases. It also addresses topics law students rarely study and on which there are few resources for lawyers and commentators, such as asset forfeiture, protest policing, video recording the police, and criminal investigations and prosecutions of police officers.

Even so, that hasn’t stopped some professors who have given her book a test run from using it in their criminal procedure courses. Harmon said that the book was not conceived with that purpose in mind, but she has grown more comfortable with the idea that it can be used to teach an alternative version of criminal procedure, one in which the police are front and center.

Harmon is a member of the American Law Institute and serves as an associate reporter for ALI’s project on Principles of the Law of Policing. She advises nonprofits and government actors on issues of policing and the law, and served as a policing expert for the independent review of the white supremacist events of Aug. 11-12, 2017, in Charlottesville, Virginia.

In December she co-authored a report, “Policing Priorities for the New Administration,” advocating for a stronger regulatory approach. The report, in collaboration with Barry Friedman and the Policing Project at the New York University School of Law, urged the White House to appoint a policing czar and require that all of the more than 80 federal law enforcement agencies meet basic standards for transparency, among other “clear and actionable” measures.

Related Scholarship

- “Reconsidering Criminal Procedure: Teaching the Law of the Police,” 60 St. Louis U. L. J. 391 (2016).

- “Federal Programs and the Real Costs of Policing,” 90 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 870 (2015).

- “Why Arrest?” 115 Mich. L. Rev. 307 (2016).

- “Limited Leverage: Federal Remedies and Policing Reform,” 32 St. Louis U. Pub. L. Rev. 33 (2012).

- “The Problem of Policing,” 110 Mich. L. Rev. 761 (2012) (awarded honorable mention in the Association of American Law Schools Scholarly Papers Competition, 2012).

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.