We won’t insult your intelligence by informing you of the news or Trump’s predictable reaction to her death.

Here though, are some interesting articles about her life and legacy for you to read when you have a spare moment.

Harvard Law School Memorial Honors Ruth Bader Ginsburg

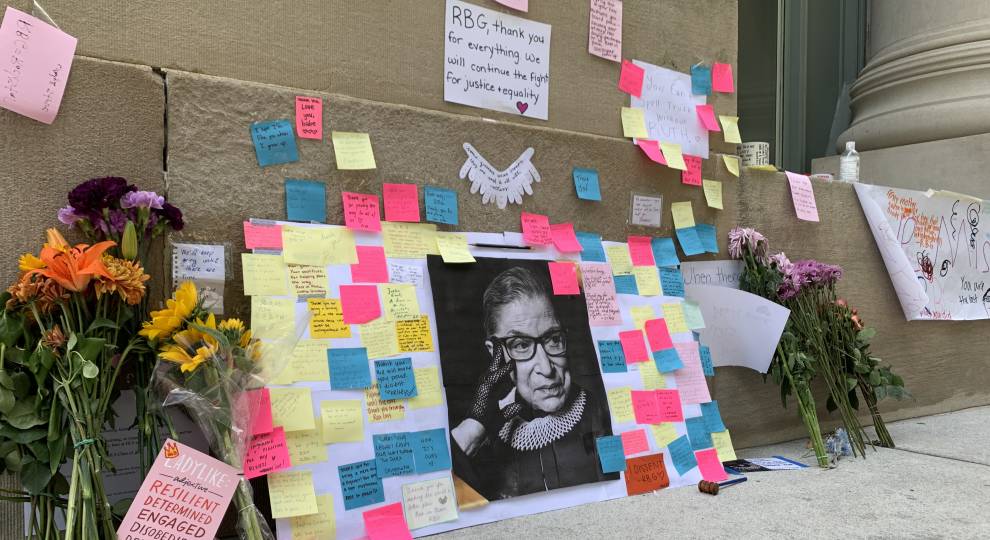

A growing collection of flowers, posters, hand-written notes and low-burning candles have accumulated on the steps of the Harvard Law School library, a makeshift memorial assembled by Harvard students and admirers of the late alumnus and Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died Friday at the age of 87.

Leaning in to read the notes, second-year Harvard Law student Jin Lee took stock of the vigil Sunday, after two days of reflecting on Ginsburg’s legacy.

“I’m just really grateful for what she has done for women in this country and for women at this school,” Lee said. “She has definitely influenced my decision to become a lawyer. She has shown me that as long as you keep pushing on the limits, they will expand. And that’s what I hope to do.”

Ginsburg enrolled at the law school in 1956, entering into a class of 552 men and only eight other women. The dean at the time famously asked the nine women, at a dinner party, why they deserved to take a place at the university that could be taken by a man. A plaque in Harvard’s Austin Hall now commemorates another discrimination those women faced: the building contained the only women’s restroom on campus, which meant female students had to run across campus to do their business and run back to make it in time for class.

Ginsburg went on to become the first female member of the prestigious legal journal, the Harvard Law Review. But after transferring to Columbia in New York, she was denied a degree from Harvard, despite completing the majority of her education there.

Notes at the memorial nodded to Ginsburg’s trailblazing legacy and the difficulties she faced leading up to her appointment as the second woman on the bench of the nation’s highest court. “Thank you for inspiring generations of women,” one note reads, scrawled on a post-it. “Lawyers and all else. We lost a hero today.”

Cambridge resident and Democratic political consultant Heidi Mitchell passed by on her daily walk with her dog, Hank, stopping to read the notes and admire the memorial.

“Obviously, it’s a pretty big blow to lose her on the court right now, and to lose her as an icon to so many people everywhere,” Mitchell said through her “VOTE” mask. “But it’s also nice to just be able to show our appreciation for everything she stood for.”

Stephanie Perez, who stopped by the memorial with her parents, said she feels a responsibility to “make a great difference in the world” in the wake of Ginsburg’s passing.

“You feel the loss of her and the legacy that she left, and you wonder who else is going to be the next person that’s going to do as much as she did for women in law,” Perez said. When asked if that person would be her, Perez’s parents nodded enthusiastically behind her. “I definitely feel a sense of duty to do something to make a difference,” Perez said. “In her name, but also, that’s why we’re all here.”

Source: https://www.wgbh.org/news/local-news/2020/09/20/harvard-law-school-memorial-honors-ruth-bader-ginsburg

Stanford Law Faculty on Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Legacy

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the legal icon who is known as the architect of the legal fight for women’s rights in the 1970s, died on Friday, September 18, 2020 at the age of 87. Justice Ginsburg was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1993 by President Bill Clinton. She was the second woman appointed to the Court, joining Stanford Law alumna retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Justice Ginsburg served on the Court for 27 years. Here, Stanford Law School faculty reflect on her legacy.

Pamela S. Karlan, Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Professor of Public Interest Law and Co-Director of the Supreme Court Litigation Clinic

Like Justice Thurgood Marshall before her, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was one of only a handful of modern Justices who would have been a pivotal figure in American constitutional law even if she had never served on the Court. As the director of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, she argued a sextet of cases in the 1970s that served as the foundation for modern sex-equality jurisprudence. Part of her tactical brilliance was to bring a number of these cases on behalf of men who were disadvantaged by stereotypical beliefs about the proper roles of the sexes. She knew—indeed, her own marriage to Marty Ginsburg, one of the nation’s most brilliant tax attorneys as well as a chef extraordinaire, showed this—that men and women can play many roles, and that stereotypes constrict everyone’s opportunities. Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975) and Califano v. Goldfarb, 430 U.S. 199 (1977)—both cases she argued—provided the basis for her opinion for the Court in United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996), reminding us that the law must not rely on overbroad generalizations about the different talents, capacities, or preferences of males and females.”

But Justice Ginsburg was a woman of many parts. To be sure, she will be remembered for a series of important opinions in sex-discrimination cases—among them, in addition to the VMI case, the Court’s opinion in Sessions v. Morales-Santana, 137 S. Ct. 1678 (2017), and a dissent in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 550 U.S. 618 (2007), a Stanford Supreme Court Litigation Clinic case, that galvanized a congressional response rejecting the Court’s cramped construction of Title VII. But she was long the Court’s go-to Justice for questions of civil procedure—a subject she taught as the first tenured female faculty at Columbia Law School.

Read full article. https://law.stanford.edu/2020/09/18/stanford-law-faculty-on-justice-ruth-bader-ginsburgs-legacy/

Notorious RBG Got Her Start in Newark

Long before she became a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, Ruth Bader Ginsburg spent nearly a decade in Newark as a professor at the School of Law–Newark, now Rutgers Law School.

Ginsburg, 87, who died today after a battle with pancreatic cancer, worked at the law school from 1963 to 1972, a period when it was at the forefront of the social justice movement.

Ginsberg had graduated from Columbia Law School in 1959 at the top of her class, but couldn’t get a job at any of the white shoe law firms that typically hired top graduates of Ivy League law schools. She landed a clerkship with U.S. District Court Judge Edmund L. Palmieri in the Southern District of New York.

https://www.tapinto.net/sections/law-and-justice/articles/notorious-rbg-got-her-start-in-newark

Watson Coleman Mourns Justice Ginsburg, Former Rutgers Law Professor

EWING, NJ – Congresswoman Bonnie Watson Coleman (NJ-12) issued the following statement upon on the passing of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg:

“I am heartbroken to learn that we’ve lost Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She was a giant, contributing to legal scholarship for over half a century from her time as a law professor at Rutgers Law School and Columbia Law School. She was an advocate for women’s rights, and a living legend of women’s leadership.

“Justice Ginsburg was one of the greatest lawyers of her generation, fundamentally changing the way the law interacted with gender. Her strength and fire inspired millions of women, across careers, backgrounds, and generations, giving them a model for breaking through barriers of all kinds. And both her legal work and opinions from the highest court have offered millions opportunities they may never have otherwise been given.

“That we’ve lost this light as we mark Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and Jews in America and around the world look to the year ahead, makes her passing all the more poignant. This is a moment of mourning for our country. My husband and I will hold Justice Ginsburg and her family in our prayers.”

Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Conflict of Laws

by Tobias Lutzi, University of Cologne

Since the sad news of her passing, lawyers all around the world have mourned the loss of one of the most iconic and influential members of the legal profession and a true champion of gender equality. Through her work as a scholar and a justice, just as much as through her personal struggles and achievements, Ruth Bader Ginsburg has inspired generations of lawyers.

On top of being a global icon of women’s rights and a highly influential voice on a wide range of issues, Ginsburg has also expressed her views on questions relating to the interaction between different legal systems, both within the US and internationally, on several occasions. In fact, two of her early law-review articles focus entirely on two perennial problems of private international law.

On top of being a global icon of women’s rights and a highly influential voice on a wide range of issues, Ginsburg has also expressed her views on questions relating to the interaction between different legal systems, both within the US and internationally, on several occasions. In fact, two of her early law-review articles focus entirely on two perennial problems of private international law.

Accordingly, readers of this blog may enjoy to go through some of her writings in this area, both judicial and extra-judicial, in an attempt to pay tribute to her work.

Jurisdiction

In one of Ginsburg’s earliest publications, The Competent Court in Private International Law: Some Observations on Current Views in the United States (20 (1965) Rutgers Law Review 89), she retraces the approach to the adjudication of persons outside the forum state in US law by reference to both the common law and continental European approaches. She argues that

[t]he law in the United States has […] moved closer to the continental approach to the extent that a relationship between the defendant or the particular litigation and the forum, rather than personal service, may function as the basis of the court’s adjudicatory authority.

Ginsburg points out, though, that each approach includes ‘exorbitant’ bases of judicial competence, which ‘provide for adjudication resulting in a personal judgment in cases in which there may be no connection of substance between the litigation and the forum state.’

Bases of judicial competence found in the internal laws of certain continental states, but generally considered undesirable in the international sphere, include competence founded exclusively on the nationality of the plaintiff – for example, Article 14 of the French Civil Code – and competence (to render a personal judgment) based on the mere presence of an asset of the defendant when the claim has no connection with that asset-a basis found in the procedural codes of Germany, Austria, and the Scandinavian countries. Equally undesirable in the view of continental jurists is the traditional Anglo-American rule that personal service within the territory of the forum confers adjudicatory authority upon a court even in the case of a defendant having no contact with the forum other than transience

The ‘most promising currently feasible remedy’ for improper use of these ‘internationally undesirable’ bases of jurisdiction, she argues, is the doctrine of forum non conveniens.

At the least, a plaintiff who chooses such a forum should be required to show some reasonable justification for his institution of the action in the forum state rather than in a state with which the defendant or the res, act or event in suit is more significantly connected.

Applicable Law

As a Supreme Court justice, Ginsburg also had numerous opportunities to rule on conflicts between federal and state law.

In Honda Motor Co v Oberg (512 U.S. 415 (1994)), for instance, Ginsburg dissented from the Court’s decision that an amendment to the Oregon Constitution that prevented review of a punitive-damage award violated the Due Process Clause of the federal Constitution, referring to other protections against excessive punitive-damage awards in Oregon law. In BMW of North America, Inc v Gore (517 US 559 (1996)), she dissented from another decision reviewing an allegedly excessive punitive-damages award and argued that the Court should ‘resist unnecessary intrusion into an area dominantly of state concern.’

According to Paul Schiff Berman (who provided a much more complete account of Ginsburg’s relevant writings than this post can offer in Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Interaction of Legal Systems (in Dodson (ed), The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (CUP 2015) 151)), her ‘willingness to defer to state prerogatives in interpreting state law […] may surprise those who focus on Justice Ginsburg’s Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence in gender-related cases.’

The same deference can also be found in some of her writings on the interplay between US law and other legal systems, though. In a speech to the International Academy of Comparative Law, she argued in favour of taking foreign and international experiences into account when interpreting US law and concluded:

Recognizing that forecasts are risky, I nonetheless believe the US Supreme Court will continue to accord “a decent Respect to the Opinions of [Human]kind” as a matter of comity and in a spirit of humility. Comity, because projects vital to our well being […] require trust and cooperation of nations the world over. And humility because, in Justice O’Connor’s words: “Other legal systems continue to innovate, to experiment, and to find . . . solutions to the new legal problems that arise each day, [solutions] from which we can learn and benefit.”

Recognition of Judgments

Going back to another one of Ginsburg’s early publications, in Judgments in Search of Full Faith and Credit: The Last-in-Time Rule for Conflicting Judgments (82 (1969) Harvard Law Review 798), Ginsburg discussed the problem of the hierarchy between conflicting judgments from different states and made a case for ‘the unifying function of the full faith and credit clause’. As to whether anti-suit injunctions should also the clause, she expressed a more nuanced view, though, explaining that

[t]he current state of the law, permitting the injunction to issue but not compelling any deference outside the rendering state, may be the most reasonable compromise […].

The thesis of this article, that the national full faith and credit policy should override the local interest of the enjoining state, would leave to the injunction a limited office. It would operate simply to notify the state in which litigation has been instituted of the enjoining state’s appraisal of forum conveniens. That appraisal, if sound, might induce respect for the injunction as a matter of comity.

Ginsburg had an opportunity to revisit a similar question about thirty years later, when delivering the opinion of the Court in Baker v General Motor Corp (522 US 222 (1998)). Although the Full Faith and Credit Clause was not subject to a public-policy exception (as held by the District Court), an injunction stipulated in settlement of a case in front of a Michigan court could not prevent a Missouri court from hearing a witness in completely unrelated proceedings:

Michigan lacks authority to control courts elsewhere by precluding them, in actions brought by strangers to the Michigan litigation, from determining for themselves what witnesses are competent to testify and what evidence is relevant and admissible in their search for the truth.

This conclusion creates no general exception to the full faith and credit command, and surely does not permit a State to refuse to honor a sister state judgment based on the forum’s choice of law or policy preferences. Rather, we simply recognize that, just as the mechanisms for enforcing a judgment do not travel with the judgment itself for purposes of Full Faith and Credit […] and just as one State’s judgment cannot automatically transfer title to land in another State […] similarly the Michigan decree cannot determine evidentiary issues in a lawsuit brought by parties who were not subject to the jurisdiction of the Michigan court.

According to Berman, this line of reasoning is testimony to Ginsburg’s judicial vision of ‘a system in which courts respect each other’s authority and judgments.’

Ginsburg’s Law Clerks Likely to Be Reassigned as New Term Unfolds

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s clerks had likely already been studying petitions that will be considered by the justices at the so-called long conference.

What Ruth Bader Ginsburg Means to the Next Generation of Legal Minds

A cultural icon in her later years, the justice inspired today’s law students more than most: ‘We’re all just hoping we can all be mini-Ruth Bader Ginsburgs in our own way’

Karla Young hadn’t yet been born when Ruth Bader Ginsburg was sworn in as the second female Supreme Court justice in 1993. But, like many women heading into the legal profession today, she says the late justice and feminist pioneer helped inspire her decision, at age 10, to become a lawyer.

“She paved the way for me to use my voice,” said Ms. Young, a 23-year-old student at Pepperdine University’s Caruso School of Law and the daughter of a Mexican immigrant.

More at (Paywall). https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-ruth-bader-ginsburg-means-to-the-next-generation-of-legal-minds-11600631280

University Of Utah Law Community Holds Vigil For Late Justice Ginsburg

Students and professors at the University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law came together Saturday night to honor the legacy of the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“Losing her really feels like losing a hero and a loved one,” said Natalie Beal, a 2nd-year law student.

It was seeing one of the most powerful positions in America occupied by the fiery Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg that inspired Beal to attend law school.

“She was very fierce in what she believed,” Beal continued. “She was very civil and kind and empathetic, but she was just a champion of so many things like gender equality.”

It’s that legacy, fought in a courtroom, with a far wider-reaching victory that students and faculty at the S.J. Quinney Law School celebrated Saturday night.

Texas A&M Law professor recalls Ginsburg’s impact

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a towering women’s rights champion who became the court’s second female justice, died Friday at her home in Washington. She was 87.

Ginsburg died of complications from metastatic pancreatic cancer, the court said.

She argued six key cases before the court in the 1970s when she was an architect of the women’s rights movement. She won five.

“She is such a great example for any law student, for any lawyer, for anyone who believes in equal justice under law, the four words that greet you as you walk into the United States Supreme Court,” said Meg Penrose, professor of law at Texas A&M Law School in Fort Worth. “I mean, I think more than any other justice besides Thurgood Marshall, she personified that in her entire career. “