Transcript

https://www.npr.org/transcripts/1197954152

SYLVIE DOUGLIS, BYLINE: NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF DROP ELECTRIC SONG, “WAKING UP TO THE FIRE”)

DARIAN WOODS, HOST:

When Fabiola Pinacue read the letter back in 2021, she was livid.

FABIOLA PINACUE: (Through interpreter) I wanted to kill them, but of course, you can’t. They’re very far away. They’re very big, and there’s nowhere to find them.

WAILIN WONG, HOST:

The letter that got Fabiola so riled up was from the Coca-Cola Company. It was a cease-and-desist letter. It said that her company had infringed Coca-Cola’s trademark, and they had 10 days to pull their drinks from the market or risk legal action.

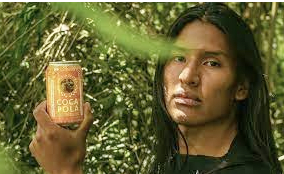

WOODS: The product in question was a beer infused with the coca leaf. In Colombia, where Fabiola lives, pola is a common word for beer, so her coca beer was called, naturally enough, Coca Pola.

PINACUE: (Through interpreter) I was very angry because they had been in the market for 100 years. I’m sorry, this has been in my life forever, and I’m a descendant of a thousand-year tradition of people using the coca leaf.

WONG: This is a common story. A corporate giant like Coca-Cola gets into a trademark dispute with a smaller company that’s been using a particular word, or it even appropriates a name that’s been used by another culture for a very long time. What’s fascinating about this story is how Fabiola fought back. This is THE INDICATOR FROM PLANET MONEY. I’m Wailin Wong.

WOODS: And I’m Darian Woods. Today on the show, an indigenous woman in Colombia makes a stand against a company that’s pretty much synonymous with transnational capitalism, Coca-Cola.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

WOODS: Fabiola Pinacue is a member of the Nasa people who are indigenous to the southwest of Colombia. And as a kid, Fabiola remembers her grandparents chewing on the coca leaf.

PINACUE: (Through interpreter) For me, the coca leaf has been one of the fundamental elements of the Nasa people’s culture.

WONG: For more than 8,000 years, the coca leaf has helped Indian people with altitude sickness, suppressed hunger, provided calcium and given moderate energy boosts. Of course, coca can also be processed to make cocaine, so the coca leaf has an ambiguous status in Colombia. On the one hand, chewing raw coca is legal in indigenous Colombian territories. On the other hand, the Colombian government has waged battles against coca. Up until several years ago, it welcomed U.S. support in spring enormous amounts of pesticides from planes in order to destroy illicit coca plantations. This harmed both locals and wildlife, and it was part of the global war on drugs.

WOODS: But it’s worth knowing that the raw coca leaf, as used traditionally, is really mild, like a kombucha compared to a bottle of rum. Yet even so, global government efforts to eradicate cocaine brought stigma to the coca leaf over the last half century or so.

PINACUE: (Through interpreter) I watched my grandparents stop chewing coca leaves, and they hid it, only using it for rituals.

WONG: And Fabiola was seeing more than just the use of the coca leaf disappearing. To her, it was symbolic of the threats to her entire culture.

WOODS: And so after going to university, Fabiola decided to start a business that would make coca products. She called it Coca Nasa. The idea would be that people would be able to buy her products like coca tea and realize it’s a fairly mild stimulant. It’s not like pure cocaine at all. It’s about as psychoactive as a cup of Earl Grey tea.

WONG: But selling coca products outside of the indigenous territories put her in a bit of a legal gray area, with the Colombian government flip-flopping between tolerating and stamping out her products there. Fabiola was even once detained for a few hours for carrying toasted coca leaves in a bus terminal. She was released without charges. Despite these obstacles, she grew the company to about 20 employees, and it became well known in Colombia.

WOODS: And then in late 2021, Fabiola receives that cease-and-desist letter on behalf of a company with 80,000 employees, Coca-Cola, a company long associated with the United States and all its global powers. And you could see, at least on the surface, why Coke might be writing this complaint – Coca-Cola, Coca Pola – pretty similar names. Jennifer Jenkins is a professor at Duke University who teaches trademark law.

JENNIFER JENKINS: Trademarks confer limited, exclusive rights over words, over symbols, over devices to brands, so that I can see Coca-Cola on a bottle and know that I’m getting the drink that I’m trying to buy from the same entity that produced that delicious, carbonated beverage in the past. So that’s good for me.

WOODS: And you’re not getting paid by Coca-Cola to say that. Let’s be clear.

JENKINS: (Laughter) Exactly.

WONG: Avoiding confusion in the marketplace is the No. 1 purpose of trademarks, and it gives companies an incentive to produce a consistent level of quality because they know their work won’t be undermined by a competitor pretending to be them.

JENKINS: And so here we have the valuable trademark rights of this company coming into conflict with another culture ’cause, you know, words have significance and meaning in multiple cultures. Certainly, the word coca will mean something different to indigenous communities in countries like Colombia, where the coca leaf is sacred, and the term coca is also sacred.

WOODS: So this case is a clash of values, clarity to the consumer versus the rights of indigenous people like Fabiola to words they’ve used for generations. Manuel Travodiaga (ph) is a Colombian trademark attorney. He wasn’t involved directly in this case, but he says that Colombia has a precedent here. In 2012, a similar case was before Colombia’s Supreme Court, its constitutional court.

MANUEL TRAVODIAGA: The constitutional court says coca is just a generic term, so coca can be used by anyone in the market. Although in other countries or in other languages might be a very distinctive term, for us it’s not.

WONG: Adding to this ruling, Manuel says there’s a bunch more arguments that Fabiola could use in defense of Coca Pola. Colombia’s constitution ensures indigenous territories have the right to make their own laws. In 2000, Colombia agreed along with Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela and Peru that new trademarks from indigenous cultures couldn’t be filed without those communities’ permission.

WOODS: This all bolstered Fabiola’s case. But Manuel says when Fabiola got that cease-and-desist letter from Coca-Cola, it was by no means guaranteed what the outcome would be if it went to court. Coca-Cola, with tens of billions of dollars’ worth of annual sales, could afford some pretty good lawyers, which is what makes Fabiola’s next decision all the more jaw dropping.

PINACUE: (Through interpreter) What we did was that we wrote a letter on the same terms and gave them 10 days. They gave us 10 days. We turned it back around and wrote the same letter back to them and gave them 10 days to respond on who gave them permission.

WOODS: Who allowed Coca-Cola to use coca in their name? The letter threatened to ban Coca-Cola from indigenous territories if they persisted. And, yeah, that would be a tiny share of Coca-Cola’s global sales, but Coca-Cola does have half a billion consumers in Latin America who would learn about this. We reached out to Coca-Cola and its lawyers, but we didn’t receive an answer.

WONG: In the end, Coca-Cola didn’t answer Fabiola either. Both Coca-Cola and Coca Pola are still on shop shelves in Colombia. It’s kind of a stalemate, which the Colombian trademark lawyer Manuel Travodiaga says might actually be the best solution for both Coke and Fabiola’s company, Coca Nasa.

TRAVODIAGA: Coco Nasa just quietly continues doing what they were doing, and the legal system in Colombia doesn’t have to take a stand. Everyone’s benefiting from the gray zone.

WOODS: Because in the end there’s one thing that can be even stronger than the law for multinational corporations – public relations.

TRAVODIAGA: It’s just bad PR. It’s just bad PR. You see the articles, and all of them are talking about Coca-Cola attacking the indigenous population in Colombia. And then the indigenous used a very good PR response. You might think you’re right, and even the law could back you up, but you just don’t risk your publicity that way. Your reputation could be harmed by this.

WONG: As for Fabiola, she says she’s concerned Coca-Cola could come after her again. She’s trying to prepare herself if that happens. But still, she is defiant.

PINACUE: (Through interpreter) They persecuted us to get us to disappear from the market, but we have not disappeared. We have remained, and here we are.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

WOODS: This episode was produced by Brittany Cronin. Melia Agudelo translated. Sierra Juarez checked the facts. Kate Concannon is our editor. And THE INDICATOR is a production of NPR.