A new book by Professor Michelle Adams details the history and impact of Milliken v. Bradley, the Detroit school desegregation case that gained national attention and a Supreme Court ruling in the early 1970s.

“Milliken v. Bradley is the case that ended the Brown v. Board of Education era,” Adams said in a recent interview. “This book is about a very important case, but it’s really about how northern Jim Crow [laws were] created, maintained, and prosecuted.”

Written for a general audience, Adams’s book—The Containment: Detroit, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for Racial Justice in the North (Macmillan, 2025)—is the product of more than 10 years of research and writing. As an expert in race and the law who was born in Detroit, Adams had long been interested in the Milliken case.

“The more reading I did, the more interested I got. At some point I decided that there was a story that I wanted to read,” Adams said. “I knew that if it was a story that I wanted to read, then I had a shot at having it be a story that other people might be interested in as well.”

Adams—the Henry M. Butzel Professor of Law and the winner of the 2024 L. Hart Wright Teaching Award—recently answered five questions about the book and the issues it addresses:

1. What made Milliken v. Bradley unusual among school desegregation cases of the time?

You can’t really understand the development of Northern Jim Crow without understanding the nexus between school segregation and housing segregation. When we think about Jim Crow, we think about the South, we think about statutes and rules and ordinances and regulations that were visible to everybody—“whites only.”

We didn’t really have these signs in the North, but what we did have were certain kinds of techniques that maintained Jim Crow. One of the most important and efficient techniques was housing segregation, which also locked Blacks out of important educational opportunities.

The Milliken case is so important because it’s really about the crux of that housing/school nexus. Michigan had a statute on the books that prohibited discrimination in schools on the basis of race, but the city and the state did it anyway. This book is about how that happened.

2. Central to the case was the concept of “containment,” which also gives your book its title. What does it mean in this context?

At its most basic, segregation says you have to stay in a particular place. Segregation could be about housing, schools, restaurants, public accommodations, et cetera. But it’s always about separation. When I think about the containment, which is a phrase that arose in the trial, it’s about creating separate spaces, maintaining and mandating separate spaces for African Americans.

That’s essentially what happened in the city of Detroit. Blacks were segregated into particular neighborhoods and areas effectively. And because they were contained in those areas, they were also contained within those schools. “The containment” ends up being part of what’s litigated in the case.The lawyers demonstrate to the judge that Blacks don’t just happen to live in particular neighborhoods. They have to live there because of different kinds of mechanisms. They’re contained within those neighborhoods.

3. What were some of those mechanisms?

From the housing perspective, there were racially restrictive covenants. Law students learn that the Supreme Court declared that racially restrictive covenants were unconstitutional in a case called Shelley v. Kraemer in the late 1940s. These covenants weren’t independent things that maybe one or two households had in a particular neighborhood. They were a form of de facto racialized zoning, which the Supreme Court had earlier declared to be unconstitutional. So in Detroit, as in many other northern and western areas, you had de facto racial zoning—the effects of which lasted even after the Court said they were unconstitutional.

There were other things going on in the real estate industry. For instance, in Detroit, we actually had two racially separate real estate brokerage associations, and they even had separate names. So if you were a Black real estate salesperson, you couldn’t get access to the white listings. You could really only show homes that were in Black areas already.

On the school side, the authorities did a bunch of things to make sure that students were racially separated. One of the ways was by zoning. Once you have these neighborhoods that are effectively racially segregated, then you zone the schools so that the students who live in the particular neighborhood can only go to the school that’s in that neighborhood. If you do that, then effectively you have racially segregated schools. Those are just a few of the ways in which this occurred.

4. Milliken found that state and local leaders violated the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court rejected the proposed remedy—busing students between the city and the suburbs. Ultimately, what did all this mean?

The district court judge ended up saying the best way to provide a remedy would be to bring in the suburban school districts, because that’s where the white students were. If that ruling had held up—and it was initially affirmed on appeal—it would’ve meant that school kids in Detroit would’ve been going to suburban schools and suburban school children who were predominantly white would’ve been going to school in Detroit.

The Supreme Court overturned the order involving the suburban districts, which meant that the school children in the city of Detroit would continue to go to Detroit schools. However, the finding that the state had been involved in segregation in the city was never overturned.

This is the ultimate legacy of the case: Even though the Constitution was violated by state and local officials, and even though it would’ve increased educational opportunities for Black children to have access to better resourced suburban schools, and even though Brown v. Board of Education and its follow-on cases said that there needed to be a meaningful remedy for school segregation. Even though all of those things are true, children in the North and largely in the West weren’t eligible for those remedies. There could be a finding of a constitutional violation, but in effect, there really wasn’t going to be a meaningful remedy.

5. What are one or two major things that you hope readers take away from the book?

The key piece to understand is that Jim Crow was a national governmental policy. It looked different in different parts of the country, but the policy itself was national. I hope readers gain a better understanding of the national policy of Jim Crow and how it operated.

A second piece is de facto versus de jure segregation. There’s this idea that in the South, there was de jure—by law—segregation, but then elsewhere it was de facto. De facto basically means that the government didn’t require segregation; it kind of just happened because people made individual private choices.

One of the key things I want folks to take away from my book is that there’s really not a distinction between those two things. It was all de jure. It was all governmentally arranged, mandated, created, and maintained.

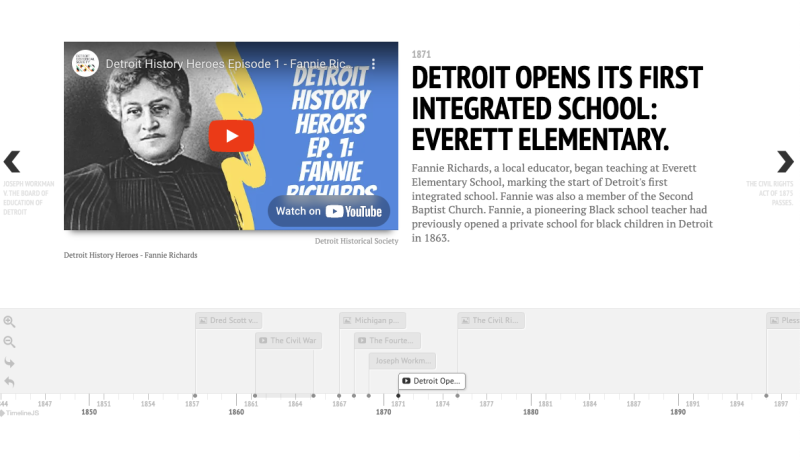

Deeper dive: Interactive timeline of Detroit school integration history

Law School students Michelle Landry and Victoria Pedri created an interactive digital timeline of Detroit school integration and segregation as part of an independent study.

With photos, videos, and news clippings, the timeline offers an incredible opportunity to learn more about this period in Detroit history.