The viewing platform vs the wealthy residents and yes the wealthy residents won out…

The Supreme Court has recently overruled the Court of Appeal and decided that the viewing platform at the Tate Modern Gallery does cause an actionable nuisance to the owners of luxury residential flats opposite.

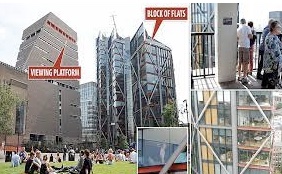

The case concerned glass fronted flats adjacent to the viewing platform of the Blavatnik Building, an extension to the Tate Modern built in 2016, after the flats had already been constructed. From the platform, hundreds of thousands of visitors each year could look straight into the flats opposite with the Court comparing the level of disruption to the residents as “much like being on display in a zoo”.

What were the Courts findings?

The Court found (by a majority of 3:2) for the residential owners, who had complained that this was an unreasonable interference with their enjoyment of their flats, and which in law amounted to an actionable “nuisance”; and against the Tate Modern, who argued that the use of their own land was reasonable.

The Court’s decision centres around the question of whether the Tate’s use of its land was not a “common and ordinary use” and whilst accepting that the Court of Appeal was right to say that merely overlooking a neighbouring property cannot amount to an actionable nuisance, this was a very particular and exceptional use of the land involving very large numbers of people physically looking into the flats, often taking photographs and posting on social media. This exceptional level of intrusion took it beyond the ordinary.

The Court also rejected the Tate’s arguments that the flat owners were responsible as they had bought properties with glass walls, and that they could but chose not to, take steps to protect their privacy by for example closing their blinds or putting up net curtains.

With liability determined – does this cause concern for developers?

Whilst liability has been determined, the issue of what remedy should be granted (whether damages in the form of monetary compensation would be appropriate, or whether an injunction should be granted to stop further nuisance), has been referred back to the High Court. This long running case therefore continues, and it remains to be seen whether the parties will reach some form of settlement before the issue of the appropriate remedy is decided by the Court, perhaps with the viewing platform being allowed to remain open subject to certain agreed restrictions.

It is unlikely that the decision will open the floodgates to claims being brought by people who find themselves being overlooked, that being part and parcel of “the rule of give and take, live and let live” for centuries. As highlighted by the Court of Appeal in its decision, “cheek-by- jowl living in cities meant that overlooking was commonplace and indeed inevitable…” However, developments going beyond ordinary residential and commercial use will need careful thought at an early design stage and the decision is likely to cause concern and uncertainty for developers planning on building anything similar.

Source: https://www.rwkgoodman.com/info-hub/the-tate-modern-a-modern-nuisance/

On a far more interesting note the Tate will be featuring in the Turbine Hall this summer , Australian Indigenous artist, Richard Bell’s work, Tent Embassy, a real legal issue to think about.

Tate

Richard Bell at the Tate Modern

In late November 2018 I was talking with Indigenous Australian contemporary artist and political activist Richard Bell in the back room of Josh Milani’s Gallery in Brisbane. Milani had been called away on business and Bell had come over from his studio to meet me. He was wearing paint-splattered shorts and a blue button through shirt. Several days of white stubble seemed to have been spray-painted onto his chin while his head was framed by a halo of wiry white hair.

A conversation with Bell is anything other than predictable. His opinions are strong, as one would expect of a long-standing activist for Indigenous rights. He doesn’t suffer fools easily. Bell eschews labels and prefers to describe himself as ‘an activist who masquerades as an artist’, a line I had heard before.

In a moment bordering on humility he reveals to Artist Profile that he has been invited to exhibit in the Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern in 2021, where previous exhibiting artists included Ai Weiwei, Anish Kapoor and Olafur Eliason.

Bell pulls no punches with his art and life which are framed in resistance and rebellion. His paintings are sometimes blocky and geometrical, sometimes abstract but always confrontational with textual statements emerging through a miasma of brilliant colour such as, We Know How To Wait (2018), and I See You As My Equal (2018), on show late last year at Milani Gallery.

When he talks about the art system and Indigenous causes it is in the lingua franca of displacement, invasion, systemised racism, and government oppression suffered by Indigenous peoples globally. White invaders You Are living on Stolen Land is a placard that sits outside his now almost iconic installation Embassy and delivers a blow like a boxer’s one-two combo.

Nowhere is Bell’s political stance more clearly articulated than in Embassy. It’s inspired by the first Aboriginal Tent Embassy, initially a beach umbrella pitched on the grounds of Canberra’s Parliament House in 1972 by four young men demanding Aboriginal land rights. Bell’s Embassy – a large army-style canvas tent – pays homage to the original and has become a place for the exchange of ideas on contemporary racism and Indigenous oppression. On its journey around the world it has become a symbol of black power and racial activism.

Read more