Imagine this piece of software being deployed globally and especially, say, in commercial courts in Asia.. game changer ?

We really hope this lot don’t succumb to having money thrown at them by Lexis and Westlaw and can somehow work out deals to take their software to other jurisdictions and apply accordingly.

I know a couple of smaller UK publishers who’d do well out of this if they could persuade Judicata to license out this tech.

Here’s what they say

Introducing Clerk

Win More Motions With Intelligent Brief Analysis

What do you get when you cross the most granular map of the law in the world with the most sophisticated and accurate legal technology in the world?

A new way to draft and understand legal briefs.

Today, Judicata is excited to introduce Clerk? —?the first software to read and analyze legal briefs: evaluating their strengths and weaknesses and identifying the ways in which they can be improved and attacked.

What You Can Measure, You Can Improve

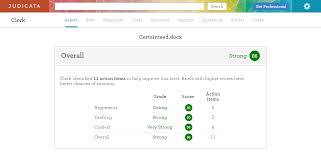

Clerk is designed to help lawyers increase their chances of winning a motion by evaluating briefs across three dimensions: Arguments, Drafting, and Context.

These dimensions involve:

- Relying on strategic and favorable arguments.

- Reinforcing those arguments with good drafting.

- Presenting the context in which the brief arises in a favorable way.

It’s important to note that a lawyer’s execution on these dimensions can be measured in an objective and consistent manner such that:

- Winning briefs perform better than losing briefs along each of these dimensions.

- Higher scoring briefs have a better chance of winning than lower scoring briefs.

This ability to grade a brief is crucial: what you can measure, you can improve.

Let’s dive into each dimension in more detail.

Arguments

Good motion practice requires the ability to craft strong arguments.

(1) Logical Favorability v. Historical Favorability

The best argued motions are those whose briefs present (a) logically favorable cases and arguments that (b) have a strong history of being followed.

The distinction between logical and historical favorability is akin to the difference between theory and practice. A case or argument may logically support a desired conclusion, suggesting why the judge should rule in a particular way. However, just because a case or argument looks favorable, that doesn’t mean it’s good to rely on.

Consider, for example, the California case In re S.B., 164 Cal.App.4th 289, 79 Cal.Rptr.3d 449 (2008). In that case, a father successfully appealed the termination of his parental rights to his daughter. In re S.B. has become one of the most frequently cited cases in California, with parents regularly analogizing their situation to that of the father, hoping to reverse the termination of their own parental rights.

But courts have grown dismissive of these arguments:

To date, In re S.B. has been distinguished over 250 times. So even though the logic of the case may be parent-friendly, in practice it’s so unlikely to win that it is a wobbly and dangerous leg to stand on.

Clerk instantaneously evaluates the cases cited in a brief to determine which are most susceptible to attack:

It would be incredibly tedious for a lawyer to do this, since it involves scrutinizing the citation network of every case cited in the brief?—?which means reviewing thousands of cases in total.

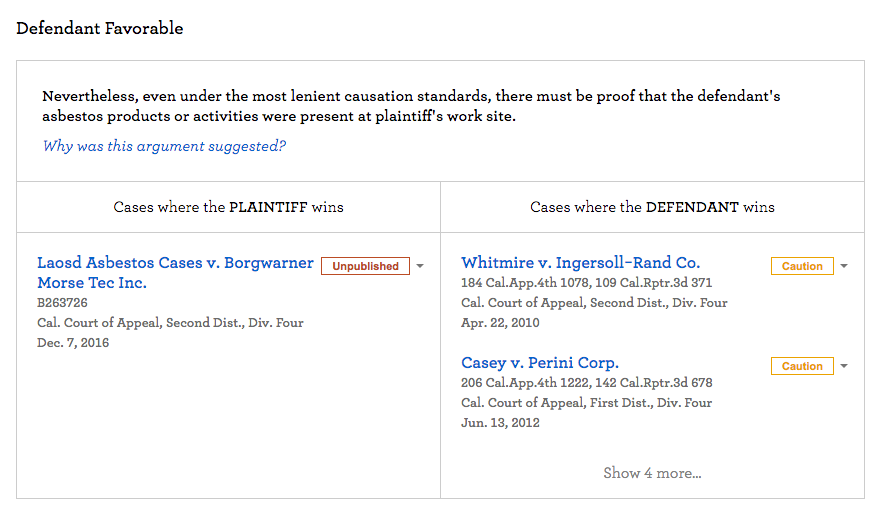

Clerk does the same type of vulnerability analysis for legal principles and arguments. It identifies the legal principles in a brief and determines whether they have historically proven more favorable for one side or the other:

This information is then aggregated to evaluate how well the overall balance of arguments supports the desired outcome of the brief:

Notably, winning briefs do a better job of relying on arguments that have previously worked well for parties in the same position.

Clerk helps lawyers improve the overall balance of arguments in their brief by suggesting additional relevant arguments that have historically worked better for the party in their position:

(2) Fair and Balanced?

While it’s critical to rely on favorable arguments and precedent, it’s also important to address (and dismantle) the opposition’s arguments and precedent. The degree to which this needs to be done depends on the posture.

At trial, the party initiating a motion does better when they devote most of their effort to presenting their own arguments. Winning briefs on the initiating side generally cite twice as many cases that support their position as their opponent’s position. By contrast, responding parties do better when their ratio of cited case outcomes is closer to 1-to-1.

On appeal, the positions are reversed. Appellants do better with a 1-to-1 ratio, while respondents find more success with a 2-to-1 ratio. Briefs that deviate too far from these underlying ratios perform worse.

Why?

Judges and clerks almost certainly aren’t counting the citations in a brief or calculating ratios. Rather, it’s that the numbers are a proxy for something deeper?—?akin to a thermometer signaling that the body has a fever. The key is to recognize that when a lawyer is filing a motion at trial, the slate is clean. They have the opportunity to set the stage and the tone. By contrast, the responding party has to not only make their own case, but also challenge their opponent’s position.

On appeal, the burdens are reversed. The lower court’s decision is the baseline, and the appellant must effectively undercut that decision while also presenting their own case. Responding to the appellant involves doubling down on the lower court’s decision.

With this context in mind, Clerk looks at the ratio of cases cited in the brief and identifies whether the balance may be off:

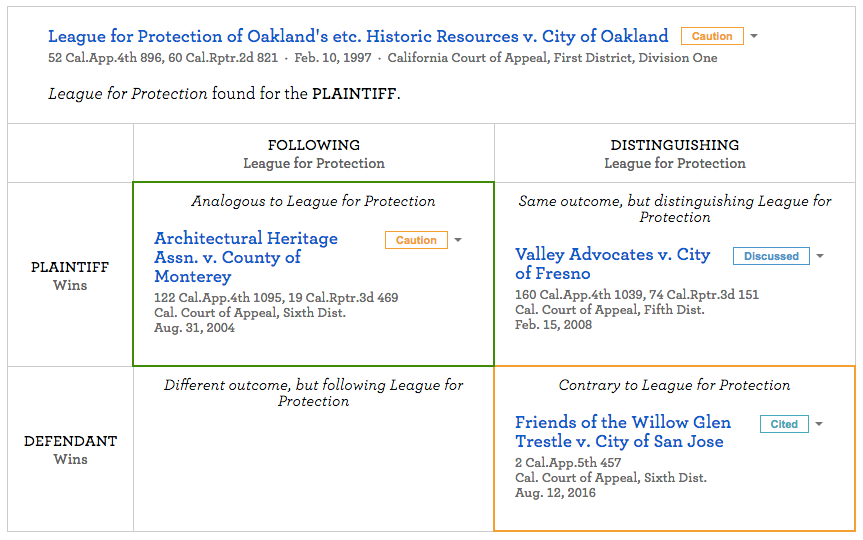

Moreover, Clerk suggests cases that can help shift the balance in a particular direction. This is done via an Outcome Matrix that identifies cases that may bolster or undermine the decisions cited in the brief.

Drafting

In addition to making strong arguments, it’s paramount that a brief present its precedents well. This is the legal equivalent of dotting every “i” and crossing every “t.”

Supporting Arguments With The Best Precedent

In the Curmudgeon’s Guide to Practicing Law, Mark Herrmann explains:

When I discuss a case in a brief, I think carefully about the persuasive force of the precedent. I prefer to cite cases where the trial court did what my opponent is seeking here, and the appellate court reversed. Judges do not like to be reversed.… The second most persuasive precedent is a case in which the trial court did what I am asking the trial court to do in my case, and the appellate court affirmed.

Statistics corroborate the judiciousness of this advice. Winning briefs do a better job than losing briefs of supporting their legal principles with cases that match the desired outcome. Moreover, as we noted in an earlier blog post on Outcome-Oriented Research:

Nearly 75% of following treatments are of cases that have the same side winning, and over 70% of distinguishing treatments are of cases that have the opposite side winning.

For certain postures, this association is even stronger. Appeals from a motion for class certification have a treatment-outcome correlation close to 80%.

Outcomes matter and courts feel compelled to address them.

But following Herrmann’s advice isn’t easy. It generally involves sifting through dozens or even hundreds of cases by hand and identifying those that apply the desired legal principle while also having the right outcome.

Clerk makes this process easy by identifying the legal principles included in a brief and suggesting better cases to rely on in support of them. These are cases that match the desired outcome of the brief, as well as its cause of action and procedural posture:

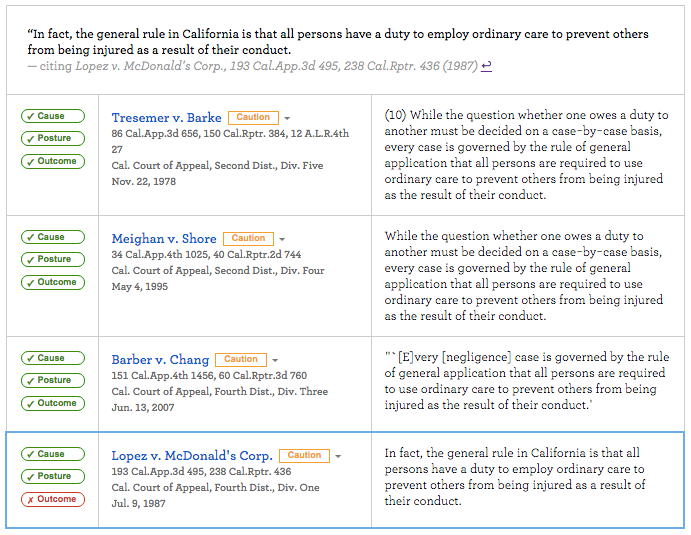

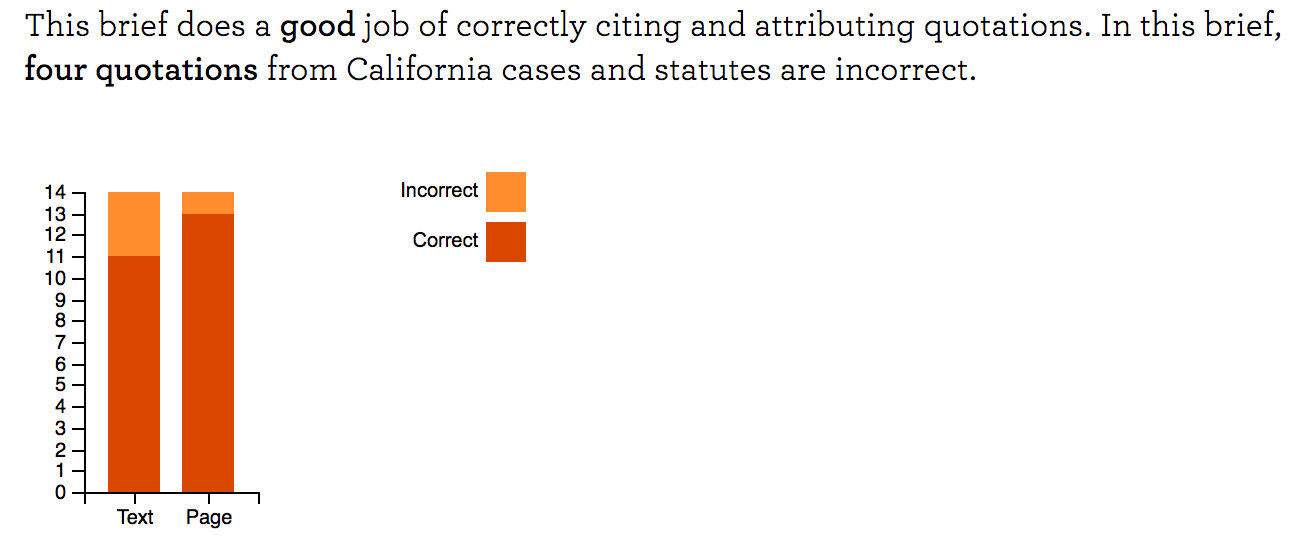

Correct Quotes

Clerk also makes it easy to correctly quote California cases and statutes. Most briefs have errors, and while sloppy briefs don’t necessarily make or break a motion, winning briefs make about 25% fewer drafting errors than losing briefs.

Clerk helps reduce these errors by identifying the quotations in a brief and cross checking them against the cited case to ensure the text is identical and the page numbers are correct.

Notably, not all quotation errors are benign. Judicata has found that many briefs have substantially modified text?—?text that changes the meaning of the quote. This includes leaving out or changing key qualifiers (such as “should,” “likely,” “may,” or “if possible”):

This also includes omitting entire phrases or key blocks of text:

Sometimes the modifications look too substantial to be unintentional, but whether a particular misquote is an inadvertent error or “creative” lawyering can be difficult to know for sure.

Context

Finally, there is a factual and legal context in place long before pen is ever put to paper in drafting a brief.

Every case has its own facts, claims, and participants. And each of those facts, claims, and participants have different odds associated with them. For example, the odds of success in front of a particular judge, and with a particular cause of action or posture, can vary.

Clerk recognizes the factual and legal context of a brief and identifies the baseline odds:

Even if the context a lawyer finds themself in isn’t favorable, that doesn’t mean that all hope is lost.

The contextual data Clerk surfaces can illuminate how a lawyer might tilt those long odds to be more in their favor. The key is finding instances where cases buck the trend, and then shaping the brief’s arguments such that the weight of authority appears to be more in their favor. Clerk evaluates tens of thousands of cases to find and suggest these needles in the haystack.

Closing Thoughts

Most of this post has explained how Clerk can help in evaluating and writing one’s own brief. But Clerk is not just a shield; it is equally powerful as a sword. Clerk provides analysis and suggestions that can help with effectively attacking an opponent’s brief. And it does this in mere seconds.

What does this mean for lawyers? It means that going forward a significant amount of a lawyer’s motion practice will be faster, easier, and better.

Welcome of the future of legal technology.

Check out a demo of clerk here. Email us if you’d like to learn more.