Journalism.co.uk reports……….In 2017, in the ongoing aftermath of Donald Trump’s election to presidency and the Brexit referendum result, journalists at German newspaper Zeit Online felt the urge to tackle its audience’s filter bubbles.

So the publisher came up with a simple-sounding idea: introduce readers to someone who thinks very differently to them and lives close by.

“It’s a bit like a political Tinder,” joked Sebastian Horn, deputy editor-in-chief of Zeit Online, speaking at the INMA Media Innovation Week in Hamburg (24 May 2019).

“You introduce people and they all meet at the same time on the same day to exchange [ideas].

“At a time of increasing polarisation, we started to build a platform to allow people to communicate.”

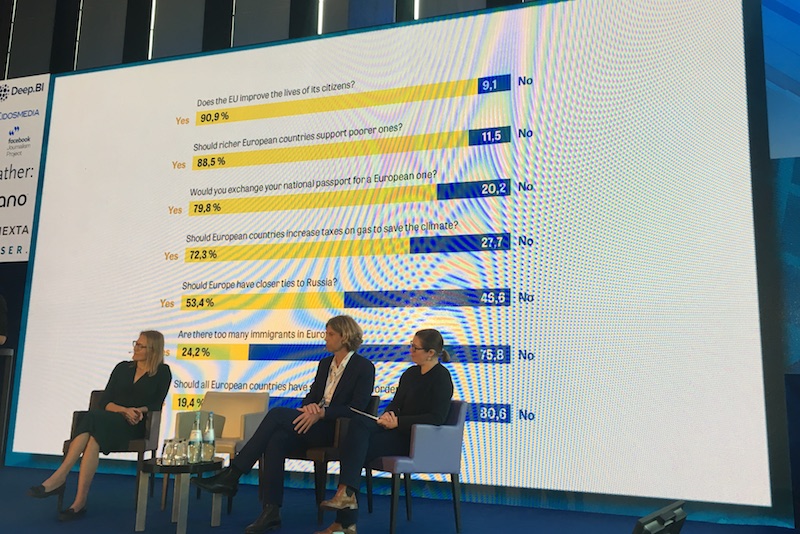

To select the pairs, willing participants answered a few questions on the newspaper’s website and were then matched to a local reader with a very different opinion on some of the biggest topics, like immigration, the EU and climate change.

As Germany Talks proved successful, it expanded to other countries like Italy, United Kingdom or Poland under different names.

The growing popularity of My Country Talks later inspired 16 publishers to come together and roll out Europe Talks ahead of the 2019 European elections. A computer algorithm paired up more than 16,200 people from 33 countries who met either face-to-face on 11 May 2019 in Brussels, or via a video call.

Two of the most obvious obstacles to meet and talk on a European level were distance and language barrier. However, participants were motivated enough to overcome both to foster dialogue.

“People want to express their political news under the umbrella of a newspaper,” said Karel Verhoeven, editor-in-chief of De Standaard, Belgium.

De Standaard also struck a collaboration with one of its competitors to illustrate the spirit of exchange and dialogue. To then reach a diverse audience, it partnered with smaller organisations.

“However,” said Aleksandra Sobczak, chief of digital newsroom at Gazeta Wyborcza, “one of the limitations was that the media organisations were quite similar and have reached a very similar readership in their respective countries.”

For Sobczak, the greatest lesson was discovering that when people argue online, they use words they would never say in the real world.

“But meeting someone in real life, we start to talk with respect because, although they have different views, we see the human being behind an opinion.”

Collaboration between journalists, whether on a national or international level, is far from straight-forward, though. It comes with challenges, like trying to communicate a single idea to different audiences, and concerns around cost and time-investment.

“You end up with a lot of journalism that you simply cannot write into your own newspaper. It is as much a branding exercise as it is a journalistic exercise,” Verhoeven added.