Fabulous piece in the Hustle yesterday….

The ‘poinsettia prince’ and the rise of a monopolyIn 1900, a German immigrant named Albert Ecke packed his bags for Fiji, where he intended to open a health spa. En route, he made a pitstop in Los Angeles and chose to settle there instead — a decision that would change the trajectory of agricultural history. Ecke and his family established a dairy farm and a fruit orchard before eventually selling cut flowers, including poinsettias. By 1909, the poinsettias were selling so well that he made them the focus of his entire business. His son, Paul Ecke, assumed the business in the 1920s and moved the operation to Encinitas, 25 miles north of San Diego. Ecke soon developed secret breeding techniques that vastly improved the durability and aesthetics of poinsettias. In the wake of the Plant Patent Act of 1930, which allowed breeders to protect their new cultivars, he registered dozens of his creations, staving off competitors and copycats. |

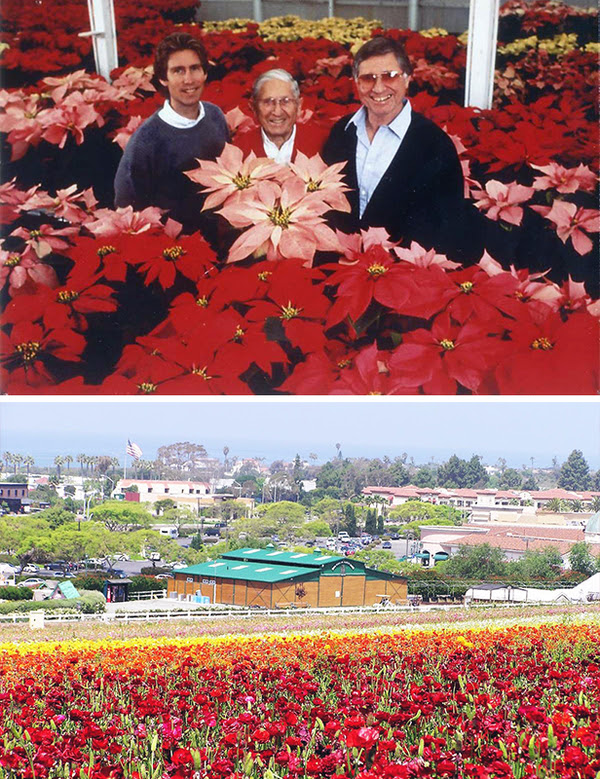

Paul Ecke Sr. with some of his harvest (The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Papers and Family Records, via CSU San Marcos archives) |

| The specifics of Ecke’s prized breeding technique — which he acquired from an amateur German gardener — were guarded with the intensity of the Coca-Cola recipe.

“Nobody at the ranch knew the secret,” his grandson, Paul Ecke III, later told the Los Angeles Times. “My grandfather, my dad, and their breeder knew, and it was done at the breeder’s home so nobody could see.” The result was a fuller, hardier plant with more branches — a product equipped to endure the tribulations of consumerism. At the same time, under the leadership of Ecke’s son, Paul Jr., the company marketed the plant as the premier Christmas decoration, sending free samples to women’s magazines and making the rounds on prime-time TV programs like “The Tonight Show.” By the 1990s, the family was selling 500k+ potted plants, and more than 25m cuttings — baby sections used to produce new plants — to other growers on a royalty basis. At its peak, the company had a virtual monopoly on the US poinsettia market, maintaining a 90% market share and 150+ patents. “The Eckes of Southern California are to poinsettias what De Beers of South Africa is to diamonds,” one reporter later proclaimed. While competitors popped up, none could challenge the exposure, prominence, and rich IP of Ecke Ranch. That is, until the worst possible scenario came to fruition. |

Top: Three generations of the Ecke family (left to right): Paul Ecke III, Paul Ecke Sr., and Paul Ecke Jr. (The Paul Ecke Ranch, Inc. Business Papers and Family Records, via CSU San Marcos archives); Bottom: Paul Ecke Ranch in Encinitas (Tripadvisor) |

| In 1992, a graduate student named John Dole got his hands on an Ecke cutting and managed to reverse-engineer the company’s top-secret process — a method that involved grafting together 2 poinsettia plants.

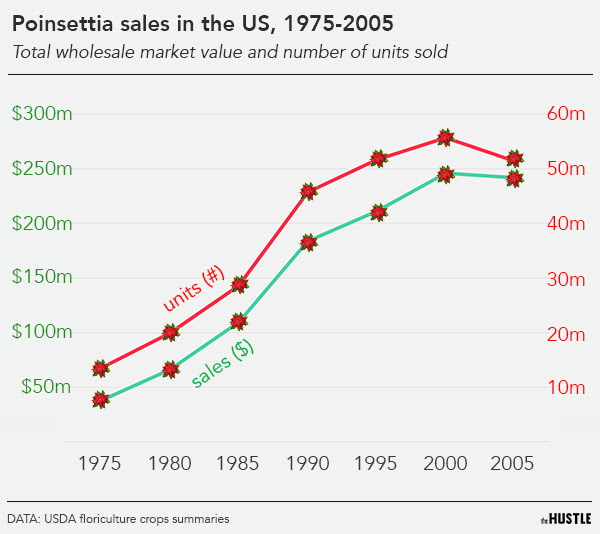

His published findings completely upended the poinsettia industry. “You don’t often see a situation in science where one paper makes a serious impact on the market,” Dole, now an associate dean at North Carolina State University, told The Hustle. “But in this case, it really did.” Competition flooded in, sparking a “golden age” for poinsettias: The industry’s main focus shifted from cultivation to breeding, and dozens of new color variations popped up — hues of white, yellow, neon green, and pink — with names like “Premium Picasso” and “Monet Twilight.” Big-box retailers also began to change the dynamic of the market. “In the earlier years, poinsettias were mostly sold at independent garden centers and were thought of as an upscale plant,” says Dole. “But when the mass marketers started selling them, that perception changed.” Home Depot, Lowes, and Walmart began purchasing vast quantities of poinsettias and selling them as loss leaders for as little as $0.99 each. |

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle |

| These changes pressured growers to ruthlessly cut overhead expenses to compete, eventually ushering in an era of consolidation. Giant agriculture firms snatched up smaller outfits and shifted production overseas.

After slowly watching its monopoly decline, Ecke — the one-time king of poinsettias — sold its business to a Dutch conglomerate in 2012. It marked the end of an era — and the beginning of a new, highly complex, international pipeline. |