Boston Uni Law School write….. The two School of Law clinics have already provided 50,000 hours of client service

A lot has happened since the first of two BU-MIT law clinics opened in 2015 to provide free legal services to MIT student innovators while giving BU School of Law students experience in the rapidly expanding fields of technology and startup law.

More than 750 MIT student teams have received support from LAW students, who have provided them with approximately 50,000 hours of client work, accounting for well over $10 million worth of free legal services.

In a major entrepreneurship competition at MIT last year, two-thirds of the finalists had benefited from the clinics’ support. On BU’s side, 44 law students worked in the clinics during the past school year and over the summer, accounting for almost one-sixth of the entire law class.

A lot of advanced computer science research can look and feel like the sort of ‘hacking’ that is prohibited by laws like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. So, often we’re helping clients stay on the other side of hacking laws.

The numbers show the importance students place on being on sound legal footing, as they bring a disruptive startup or revelatory research paper into the world. It was an easy decision in May for the two schools to renew the clinics’ operations for five more years.

“For a startup or an academic researcher, it’s not knowing [about potential issues] that can be the most paralyzing thing,” says Andrew Sellars, a LAW clinical instructor who directs the Technology Law Clinic at BU. “What we offer is we can give them the map. We can say here are the legal issues, here’s where the law is pretty settled, here’s where the law is unsettled, here are some things to do to mitigate your risk. And by doing all that we can add some extra confidence and energy to the venture.”

Coming into form

BU and MIT’s collaboration began in September 2015 with the launch of the first clinic targeted towards entrepreneurs and supporting students as part of a new Entrepreneurship, Intellectual Property, and Cyberlaw Program at BU. A year later, the second clinic began operations as planned, focusing on complex student needs in the technology area. Both clinics, at their founding, consisted of a supervising lawyer and eight student advocates.

“What we realized pretty much immediately was, that wasn’t going to do it—we needed to grow,” Sellars says. “And the major story of the last four years has been figuring out what the needs are and growing to meet those needs.”

Today both clinics provide an expanded level of service. The Startup Law Clinic helps student entrepreneurs navigate issues associated with launching a venture, like establishing a corporation or LLC, securing intellectual property, and hiring employees. The Technology Law Clinic, whose client base includes researchers as well as entrepreneurs, helps ensure students’ work aligns with laws around data collection, privacy, information disclosure, encryption, and more.

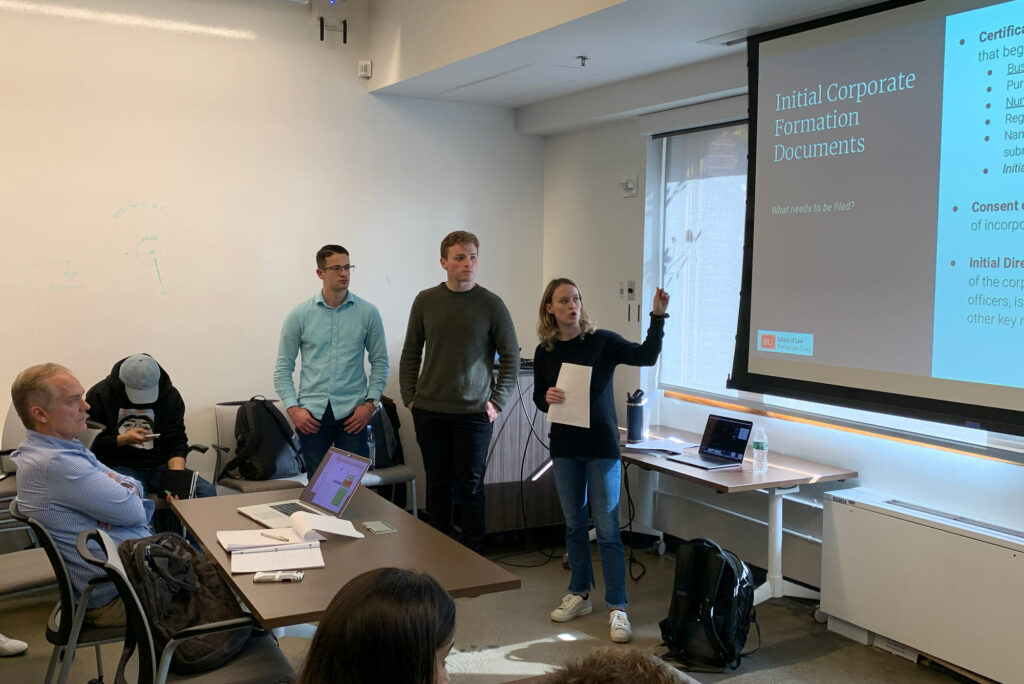

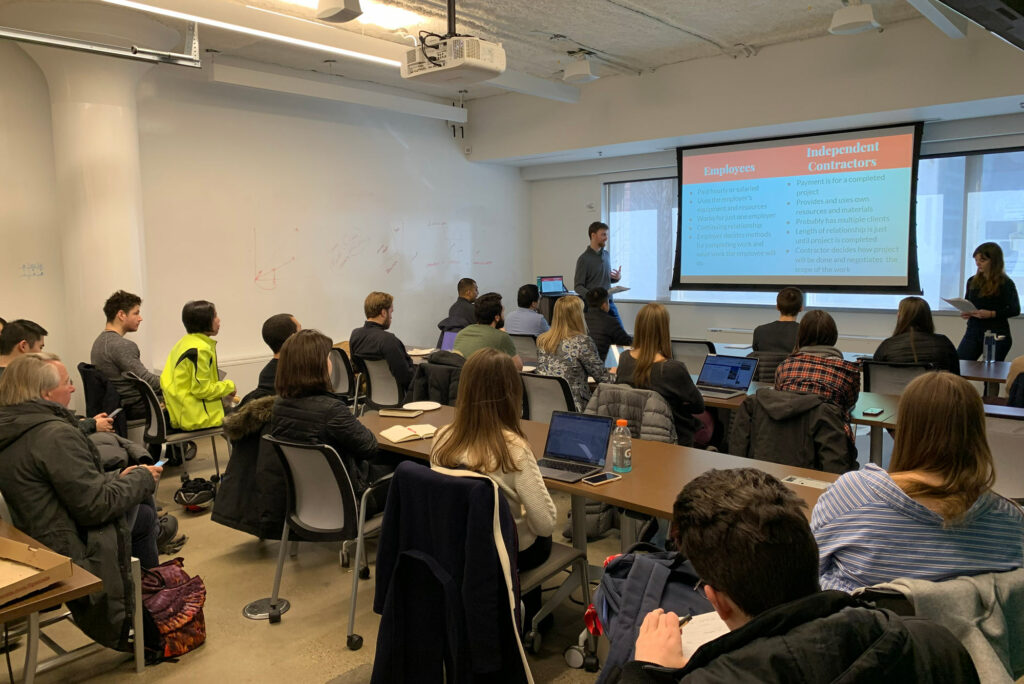

Each clinic includes three licensed attorneys, although BU’s law students do most of the work advising and representing clients. The students also write white papers on specific legal areas and conduct presentations at locations around MIT, including the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship and the MIT Media Lab, to reach a broader audience. The clinics hold regular office hours at the Martin Trust Center, the Media Lab, the MIT Sandbox, and elsewhere at MIT, making it easy for MIT students to access clinic services. They also do similar work for BU clients at the BUild Lab and elsewhere.

“Our goal is to educate our law students to do the work and have the client relationships, although we’re there supervising,” says James Wheaton, a LAW clinical associate professor who became director of the Startup Law Clinic in 2018.Since 2017, the collaboration has been bolstered by the Matthew Z. Gomes Fellowship Fund, a program that supports students from underrepresented communities in order to foster greater diversity among the next generation of technology and startup lawyers. Four of the seven fellows working for the clinics this summer are Gomes Fellows.

“The tech sector has known this about itself for some time: We have a major diversity problem in all corners of tech, including in the lawyers who represent tech companies,” Sellars says. “We wanted to think of some ways to improve diversity in technology by improving the pipeline.”

Legal support for impact

In 2014, MIT PhD candidate Amy Johnson filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the CIA seeking information about the agency’s Twitter account. When the CIA failed to produce any documents, Johnson worked with the Technology Law Clinic to file a lawsuit against the agency, which sent her just 30 documents related to her request.

Johnson and her legal team decided that wasn’t enough, and, after several more rounds of litigation, she has now received approximately 400 records. That case is ongoing and Johnson is still seeking more documents.

“We really kicked in the door by suing the CIA our first year,” Sellars says.

The CIA case is one of several high-profile projects the law clinics have been involved with. The Technology Law Clinic also helped MIT researchers publish a study revealing bias in multiple companies’ facial-analysis programs. The study showed the algorithms had an error rate of just 0.8 percent for light-skinned men but 34.7 percent for dark-skinned women. The clinic helped the researchers ensure the study complied with computer access laws and to coordinate disclosure of the results of the study with the companies in advance of its publication.

More recently, the clinic helped researchers in MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory as they published technical papers that exposed security vulnerabilities in a mobile voting application that had been used in the 2018 midterm elections. The vulnerability gave hackers the opportunity to alter, stop, or expose how users voted.

“A popular area we work in is computer science, both because of the huge population of CS students at MIT, and also because a lot of advanced computer science research can look and feel like the sort of ‘hacking’ that is prohibited by laws like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. So, often we’re helping clients stay on the other side of hacking laws,” Sellars says. “Then there are a lot of data-related questions…[dealing with] data privacy, access to data, use of data, and web scraping, which is writing a script that systematically gathers info across the web.”

While the field of computer science accounts for a large portion of the clinics’ work, students from across MIT’s campus have benefited from the clinics’ support, something people familiar with MIT’s innovation ecosystem expected from the start.

“I’m not surprised at all that the clinics have supported students from all five of MIT’s schools,” says MIT’s David H. Koch Professor of Engineering Michael Cima, who also serves on the board of the clinics. “Student-led startups, in particular, are very diverse in their makeup. These include not only for-profit oriented businesses, but also sustainable nonprofits.”

Benefits for the future lawyers, too

The clinics provide the BU students with invaluable practical experience in increasingly important areas of the law. Felicity Slater (LAW’22), who joined the Technology Law Clinic in May, has worked with seven different clients across a wide array of MIT departments.

“Several of the clients that I’m working with are graduate student researchers at the Media Lab, doing truly unique and fascinating research,” Slater says. “I’m also working with a few clients who are starting businesses, and I assisted an MIT undergraduate with an employment law question. I’m finishing out my summer by working on a dispute about a Freedom of Information Act request that is in active litigation.”

It’s “pretty revolutionary” to have the opportunity to work with real clients, Slater notes. “It brings the work alive and makes everything—the research, the writing, the editing—more meaningful,” she says. “I’ve thought about how the uncertainty and trepidation that people can sometimes have around the law—Can I do this? Is this legal?—can cause stress, and make people hesitant to take on interesting and important work.”

Slater says she’s become increasingly interested in pursuing a career in tech law in some form, but is also committed to doing work that promotes civil rights. “I’m going to be a research assistant for LAW professor Danielle Citron next year,” Slater says, “and I am really looking forward to learning more about her work on cyber civil rights.”

The disruptions caused by COVID-19 have forced everyone to adjust to remote work, but they haven’t slowed the law clinics’ work in support of innovation at MIT. In fact, April 2020 was the busiest month in the clinics’ history, and they’ve continued to see a dramatic increase in work as students pursue ideas to help with the pandemic.

Now that the clinics have been renewed for five more years, their directors are brainstorming ways to further expand their services. The pandemic has shown the clinics can work even if members can’t meet in person, and has reinforced the idea that technology can help scale operations.

“We know no matter how big we grow, the program will never fully meet the needs of the MIT student body, and because of that we’re trying to think of more ways to have an impact, even if you’re not a client,” Sellars says, noting the clinics have started work on guides and “how to” documents for students that will be offered on the clinics’ websites.

“The clinics have been successful teaching and learning labs for both MIT and BU students, and have helped our students advance their passion for innovation and entrepreneurship,” says Mark DiVincenzo, vice president and general counsel at MIT. “The issues have been varied, cutting edge in many ways, allowing BU students to assist MIT students in projects that are [impacting] or will impact the world.”

Source: https://www.bu.edu/articles/2020/bu-and-mit-renew-partnership-on-technology-law/