Detention by non-state armed groups is a widespread, diverse, and legally complex occurrence in armed conflicts across the globe. In 2023, the ICRC assessed that around 70 non-state armed groups in non-international armed conflicts have detainees. The circumstances of detention can pose serious humanitarian concerns, including ill-treatment and inadequate living conditions for detainees.

In this post, part of a series on the Fourth Geneva Convention and the internment of protected persons and drawing upon the 2024 ICRC Challenges Report, ICRC Legal Adviser Tilman Rodenhäuser discusses the prohibition of arbitrary detention under international humanitarian law (IHL) and how this relates to internment by non-state armed groups in the context of non-international armed conflicts.

Any deprivation of liberty has a significant impact on the detainee and their family. Detainees are at risk of IHL violations, such as ill-treatment, enforced disappearance, sexual violence, extrajudicial killing and poor conditions of detention, including insufficient food (leading to malnutrition), and lack of access to health care and other basic services. The ICRC has also observed that detainees experience additional stress and anxiety if they do not know why and for how long they will be detained, or how to challenge their detention.

From an international law point of view, a lot can and must be said on detention by non-state armed groups.

Judicial and procedural limits on detention by non-state armed groups

No rule of IHL prohibits detention by non-state armed groups as such. In fact, IHL is built on the assumption that all parties to armed conflict will detain, and therefore sets limits to such detention.

For instance, under IHL some forms of detention, namely hostage taking in the context of an armed conflict, are always unlawful and constitute a war crime. Other forms of detention – such as detention under criminal law by parties to an non-international armed conflict – are regulated in some detail under IHL (see common Article 3 and Commentary (paras 725–731), Article 6 Additional Protocol II, and customary IHL). In addition, arbitrary detention is prohibited under customary IHL. This prohibition aims to prevent detention that is outside any regulatory framework and would leave the detainee solely in the hands – and subject to the decisions of – their captor.

The ICRC takes the view that when non-state armed groups detain people for security reasons and outside criminal procedures, they must, in order to avoid arbitrariness, provide the grounds and procedures for such internment. Grounds and procedures for internment are, however, not defined in IHL applicable to non-international armed conflicts. Since 2005, the ICRC has used institutional guidelines to provide a framework – as a matter of both law and policy – for its operational dialogue on the issue (here, Annex 1).[1]

Grounds and procedures for internment in the practice of non-state armed groups

With a view to preventing arbitrary detention, the ICRC recommends that when a non-state armed group interns anyone it must establish a framework regulating internment – one that defines the grounds (i.e. the reasons) on which a person may be interned – and a review procedure. To be effective, grounds and procedures for internment must be established in a set of rules that are respected by the detaining party: these rules can take the form of ‘law’, a code of conduct, general orders or something similar.

Under IHL, internment is considered an exceptional measure, and one that has to be justified for each individual internee. In practice, non-state armed groups have frequently concluded that there are imperative reasons of security to detain ‘soldiers’ or ‘fighters’ of an adversary; people taking up arms against the group; ‘spies’ or ‘collaborators’ working for or with an adversary; and people planning to commit, or committing, acts of sabotage or other serious harm against the group.

In other cases, however, imperative reasons of security that could justify internment do not exist. In the view of the ICRC, people may not be considered to pose an imperative security threat solely because they belong to the same family as the soldiers or fighters of the adversary; work for the adversary in a non-military capacity; support the adversary politically; share the adversary’s ideology or religion; live in a territory controlled by the adversary; or provide the adversary with food or medical care (here, p. 56). The internment of people on such grounds is unlawful.

When a person is interned, a review procedure is needed to prevent arbitrariness. It should include informing the person of the reasons for their internment, allowing the person to challenge these reasons, and reviewing such challenges and the need for internment regularly in an independent and impartial manner (here, paras 761–762; here, pp. 54-57). IHL does not define who should conduct the review, and the ICRC knows of only a few instances in which non-state armed groups have conducted internment reviews.

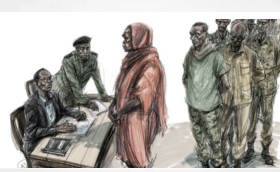

The ICRC has observed that in some instances, non-state armed groups have used a court, commission, board, religious authority or some similar mechanism to conduct reviews. These have involved (military) judges, commanders, civilian members of the armed group, lawyers, or religious leaders (here, p. 57). Under customary IHL, an internee must be released as soon as the reasons for their internment no longer exist.

Prioritization when facing limited resources and large numbers of internees

The ICRC recognizes that implementing procedural safeguards for internees may be particularly demanding for groups with limited non-military capacity and resources. However, such reviews are essential to prevent or limit the suffering caused by arbitrary detention, and to effect the release, as soon as possible, of anyone who may not be detained.

In practice, reviews should be conducted first for people with vulnerabilities (wounded or sick people, people with disabilities, children, pregnant women), ordinary civilians, and civilians associated with the adversary but not in a combat capacity. It may often be questionable that these people pose an imperative security threat. Therefore, any decision to intern them must be preceded by a thorough review process in which the internee should, wherever possible, be provided with legal assistance.

The security threat posed by a uniformed and armed soldier or fighter in a non-international armed conflict may be less controversial, but that may change, for instance, if conflict dynamics shift, the conflict ends or if the interning party receives reliable assurances that the person will no longer participate in the fighting. Thus, regularly reviewing the necessity of their internment is also important.

Ending arbitrary detention by non-state armed groups

Treating detainees with dignity and in accordance with international humanitarian law is first and foremost the obligation of their captors, be they state or non-state forces. They are accountable for violations of the law, in particular those that amount to war crimes or crimes against humanity. Ending arbitrary detention is their obligation.

Other actors should, however, also take steps to end arbitrary detention by non-state armed groups.

Many groups receive support from states. As outlined by this author and other experts elsewhere, states providing support, or states that partner with armed groups in military operations, have both a legal responsibility and often the capacity to help detaining authorities to fulfil their legal obligations and to prevent or end arbitrary detention. The ICRC has published a set of practice-based recommendations of measures that supporting states should take to ensure the lawful treatment of detainees in the hands of partners.

In addition, an ‘impartial humanitarian body, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, may offer its services to the Parties to the conflict’, be they state and non-state parties. In practice, this means the ICRC engages with non-state armed groups, as it does with all parties to armed conflict, to ensure that the dignity and physical integrity of detainees are respected and that they are treated in accordance with IHL and humanitarian principles. This includes the prohibition of arbitrary detention.

The ICRC has done just that for longer than the 75 years that the Geneva Conventions of 1949 exist – and today it continues to do so by drawing on IHL, practical experience, religious law and local customs and using various tools.

References

[1] While not all guidelines present legal obligations, and are meant to be implemented in a manner that takes into account the specific circumstances at hand, compliance with these guidelines is one means of avoiding arbitrary detention.

See also

- Tim Wood, Procedures for internment review under the Fourth Geneva Convention: reflections from New Zealand, September 19, 2024

- Ellen Policinski, War’s long legacy: the continued importance of the Geneva Conventions 75 years later, August 8, 2024

- Camilla G. Cooper, Internment pursuant to the Fourth Geneva Convention during an international armed conflict: practice and reflections from Norway, June 6, 2024

Source:

Internment by non-state armed groups: legal and practical limits