TulsaWorld reports…

As part of its efforts to commemorate the 100th year since the Tulsa Race Massacre, the Oklahoma Bar Association dedicated the bulk of its May journal issue to stories about Black Oklahomans and legal achievements they’ve made since statehood.

Among the most notable findings, according to one researcher: Oklahoma at one point before 1921 had more Black lawyers practicing than any other state — estimated at more than 60, at least four times the number in Texas at the same time. Then came the events of May 31 and June 1, 1921.

“This underscores how much of a land of opportunity Oklahoma was for so long for Blacks,” said researcher John Browning, a lawyer and retired judge who is licensed to practice law in Oklahoma and Texas.

“Oklahoma was famed for, among other things, having a number of all-Black communities and having opportunities, like in Tulsa, for Black people to have greater economic upward mobility.”

Browning, who helped curate the Oklahoma Bar Association Journal’s May issue, wrote about three of the state’s earliest Black lawyers and their work before the massacre occurred in 1921. The list included Sugar T. George, who represented a town as a member of the Muscogee National Tribal Council in 1868 and later a judge who — after having been born into slavery in Georgia — was known as being successful in the field before he died in 1900.

Another of Oklahoma’s first Black lawyers, George Napier Perkins, was also born into slavery in Tennessee but moved to Oklahoma in the 1890s to practice law. However, Perkins opted to start a newspaper in Guthrie — which became a guide for Black people seeking to move to Oklahoma — after unsuccessfully running for elected office amid a climate of racial discrimination.

Browning’s chronology also showed Perkins repeatedly lobbied for the repeal of the Jim Crow-era grandfather clause, though he died before the U.S. Supreme Court did so.

Finally, Kentucky resident William Henry Twine was among the first Black lawyers in Texas before moving to Chandler in 1891 during the Sac and Fox Land Run opening. He opened a law firm with two partners and was the first Black attorney admitted to practice in U.S. District Courts from Indian Territory before also deciding to enter the newspaper business.

Twine additionally helped create the Oklahoma Anti-Lynching Bureau in 1905 and pushed for more social acceptance of Black lawyers, writing about his and others’ exclusion from Bar Association Activities based on their race.

As Jim Crow laws continued to take effect, Browning said the research he’s found shows it became exceedingly difficult for Black lawyers to pursue a legal career. And by the 1940s, a separate Bar Association for Oklahoma-based Black lawyers was no longer in existence.

In another law journal article from OU Law professor Cheryl Wattley, she detailed the case of Ada Lois Sipuel, a Black woman who sought admission to the university’s law school and had to take her fight to the U.S. Supreme Court. Wattley said the case was a precursor to the landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

She said segregation played a role in the creation of a separate law program named the Langston School of Law, which she said was “farcically heralded as ‘substantially equal’ to the one in which white students could enroll. The school’s existence was cited as the basis for OU Law to deny Sipuel admission to its law school with white students in 1948.

“The Langston School of Law consisted of three rooms rented in the state Capitol, including a classroom that was a converted storage closet,” Wattley wrote. “Resolutions were passed adopting the OU law school bulletin and course descriptions. An agreement was made that Langston Law School students would be allowed access to the state Capitol law library. A part-time dean and two part-time professors had been hastily hired.”

The U.S. Supreme Court later found that Black students had a right under the 14th Amendment to an education and could secure admission “as soon as it is afforded to any other applicant.” The opinion resulted in Dr. George McLaurin, whose argument cited the opinion in Sipuel’s case, becoming the first Black student to enroll at OU.

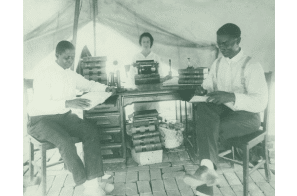

Tulsa World archives from the Oklahoma Historical Society included a photo of Tulsa attorney B.C. Franklin — the father of historian John Hope Franklin — working out of a tent after the attack on Greenwood destroyed his office in 1921. While an attorney, Franklin successfully challenged an ordinance that would have limited the materials that could be used to restore the Greenwood District based on the belief it would prevent Black residents from acquiring resources to rebuild.

Franklin became known in his career for helping those, like him, who lost their possessions during the massacre. His account of events has received renewed attention in recent years, but a little-known 1926 Oklahoma Supreme Court decision on an insurance dispute case filed by William Redfearn, a white building owner in Greenwood, also contains significant details.

“On the criminal end there were no white people charged criminally, but a number of African-Americans were charged with inciting the riot,” Browning said of the situation. “Ultimately those were dropped but that just goes to show how upside down the treatment by the legal system was.”

He said the record in Redfearn’s case, though not a criminal matter, revealed local authorities were “not just passively standing by but actively participating in the violence” against African-Americans at the time.

Redfearn had appealed a verdict in favor of his insurance provider, which had a clause indicating the policy did not cover losses caused “directly or indirectly” by invasion, insurrection, riot, civil war or commotion, or military or usurped power, or by order of any civil authority.”

The record notes the “conflicting narratives of white and Black Tulsa” in testimony provided for the case.

“The evidence shows conclusively that there was rioting in the city of Tulsa from about 10 o’clock p.m., May 31, 1921, until about noon of the following day; and during that time all the buildings in the negro section of the city of Tulsa, where the buildings involved in this suit were located, were entirely destroyed by fire,” the appellate court wrote.

Browning said many records about the violence either disappeared or were forcibly removed, which was why it was unusual to see the 1926 Supreme Court decision in Redfearn’s case have so many details about the massacre.

He said he was hopeful the information contained in the journal is informative about lesser-known aspects of Oklahoma’s Black history.

“I think everybody in society would benefit from knowing more about this aspect of our history, this aspect of Oklahoma history and certainly this aspect of tragic events like the Tulsa Race Massacre,” he said. “ A lot of people look to us lawyers as leaders in the community and sometimes we as lawyers are less informed than we’d like to be.

“I thought it would be a service to the Bar to put this information out there and a service to the community as a whole.”